Daoyin Qigong – A Simple Description and Defining Points

Daoyin, in China, denotes “The original healing way”, or “ways”, as it is the name given to those ancient practises said to have been used and developed by the people of the Chinese central region and from which medicine later evolved. As they lived in a zone described as climatically moderate, these people were able to keep healthy by the use of equally moderate and relatively subtle methods – manual techniques of massage and physical adjustment combined with physical exercise, breath regulation and meditation. This classical image represents both the natural beginnings of healing and an idealised image of harmony between human beings and their environment.

In the regions of the North, South, East and West, where the various climatic extremes caused people to suffer different diseases, further methods of treatment were developed that corresponded with local needs and resources. Thus the use of herbal remedies, needles (acupuncture), and heat cauterisations (moxabustion) were added to the medical repertoire. This classical view of the origins of Chinese Medicine, a mixture of common sense and tradition, upheld the moderate healing methods of “the Centre” as an ideal towards which all healing strategies should be aimed. The centre functions in Chinese thought as a representation of higher cultural elements.

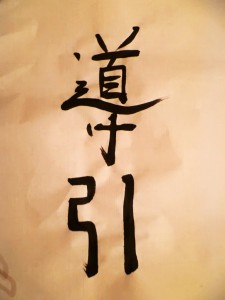

A literal translation of Daoyin helps us understand its practical significance in relation to those techniques:

Daoyin suggests that deep tranquility, or calm, is a primary healing principle, realised through attentive and careful movements. The two Chinese characters that make up the term ‘Daoyin’ are different from those that signify “The Great Tao” of Lao Tsu and the ‘Yin’ of “Yin and Yang”. Together, these characters are usually translated as “guiding and inducing” which relates directly to fostering the circulation of vital energy (Qi) and suggests certain attitudes or qualities that we can bring to our practice – precise attention, gentle encouragement, or careful determination – which will augment and guide the Qi in its path.

Does the Qi need such guidance? Perhaps not, but we ourselves are guided through the practice to relax.

The characters taken individually bring this deeper meaning to light and help our understanding and practical application of Daoyin. ‘Dao’ is stillness or deep calm, regarded as the principle ingredient of the Qigong “prescription”. But how can we access and absorb this benign influence, conducive to the harmonious flow of Qi, when long habit in the face of disturbing and agitating influences, physical or emotional, internal or external, has led to a state of deep defensive tension?

So we come to the significance of ‘Yin’, which implies the “movement characteristics” inherent in Daoyin practice. Daoyin exercises are characterized by continual slow, smooth movement guided by postural principles. So ‘Yin’ can mean “going ahead” or “leading the way”, hence “guidance”; more literally, it can be taken as “pulling”, like pulling something out or along. Mostly, we are unable to “simply be calm”, so the method is to seek inner calm little by little, as we engage in action. The form and movement in every exercise serve as the vehicle by which more subtle and hidden qualities are drawn out. Relaxation and inner peacefulness or tranquillity may be recognised and developed only by experiencing and transforming their opposites, recognised as both the controlled requirements of the exercise and any tension, agitation and haste we feel in our practice.

So we come to the significance of ‘Yin’, which implies the “movement characteristics” inherent in Daoyin practice. Daoyin exercises are characterized by continual slow, smooth movement guided by postural principles. So ‘Yin’ can mean “going ahead” or “leading the way”, hence “guidance”; more literally, it can be taken as “pulling”, like pulling something out or along. Mostly, we are unable to “simply be calm”, so the method is to seek inner calm little by little, as we engage in action. The form and movement in every exercise serve as the vehicle by which more subtle and hidden qualities are drawn out. Relaxation and inner peacefulness or tranquillity may be recognised and developed only by experiencing and transforming their opposites, recognised as both the controlled requirements of the exercise and any tension, agitation and haste we feel in our practice.

The benefits of this transformation are steadily “delivered” to the needs of the situation, either in the self-directed movement of Daoyin exercises or in the use of Daoyin treatment techniques. Even the subtle movements of the breath, the arousal of emotion, or the flow of conceptual thought in meditative awareness, serve this end. We use all movement to find our still centre. As the practices reveal subtle conflicts and tensions, we learn how to relax more deeply, and this in turn facilitates harmony among the multitudinous energetic functions of our being. This is a profound application of the Yin-Yang dialectic approach.

Nowadays, in China, the word Qigong has been generally adopted for all kinds of exercises related to health as well as for special training in medical techniques, where traditional massage and manipulations, Anmo Tuina, are combined with theories and principles of Qi in treatment. Daoyin is not such a commonly used term, but it is still associated with the specifically remedial applications of Qigong, and especially with exercises that can be taught to patients and practiced by them to aid in their own recovery. Such exercises embody the same essential principles of relaxed movement, breath regulation and calm attentiveness that we have mentioned, and it is often acknowledged that these qualities are the effective element, rather than the particular form the exercise takes.

Nowadays, in China, the word Qigong has been generally adopted for all kinds of exercises related to health as well as for special training in medical techniques, where traditional massage and manipulations, Anmo Tuina, are combined with theories and principles of Qi in treatment. Daoyin is not such a commonly used term, but it is still associated with the specifically remedial applications of Qigong, and especially with exercises that can be taught to patients and practiced by them to aid in their own recovery. Such exercises embody the same essential principles of relaxed movement, breath regulation and calm attentiveness that we have mentioned, and it is often acknowledged that these qualities are the effective element, rather than the particular form the exercise takes.

These same qualities are communicable through certain Qigong treatment methods when postural guidance may be combined with subtle touch, or simply the focussed presence of an experienced practitioner. Many people who recover from their own illnesses find they have the potential to help others because, in their more harmonious state, their whole being radiates and communicates clearer and more coherent energy or information.

All the preceding explanation has been concerned with what we can recognise as the “Medical School” within the broad campus of Qigong. This tradition, most precisely linked with healing, is one of the four important streams or “schools” within contemporary Qigong practice, the others being the Martial School, the Buddhist School and the Taoist School. (There are some who include a “Confucian” school). These are not now strictly distinguished, indeed there is considerable historical and symbolic cross-over, but they are an attempt to acknowledge the distinct sources to which Qigong owes its origin. Their common aim is to harmonise the Qi – all the vital forces of the organism – and thus to attain optimum physical and psychological health and resistance to illness. The “Inner School” of the martial arts, of which Taiji is the best known, has always shared this objective but uses fighting skills and principles as a reference for understanding and directing subtle forces.

However, Chinese medicine developed and used exercise related to medical theories alone (e.g. of Internal Organ functions and their related Channels). Daoyin represents both the early origins of this traditional practice and an important reference and guide for its ongoing use.